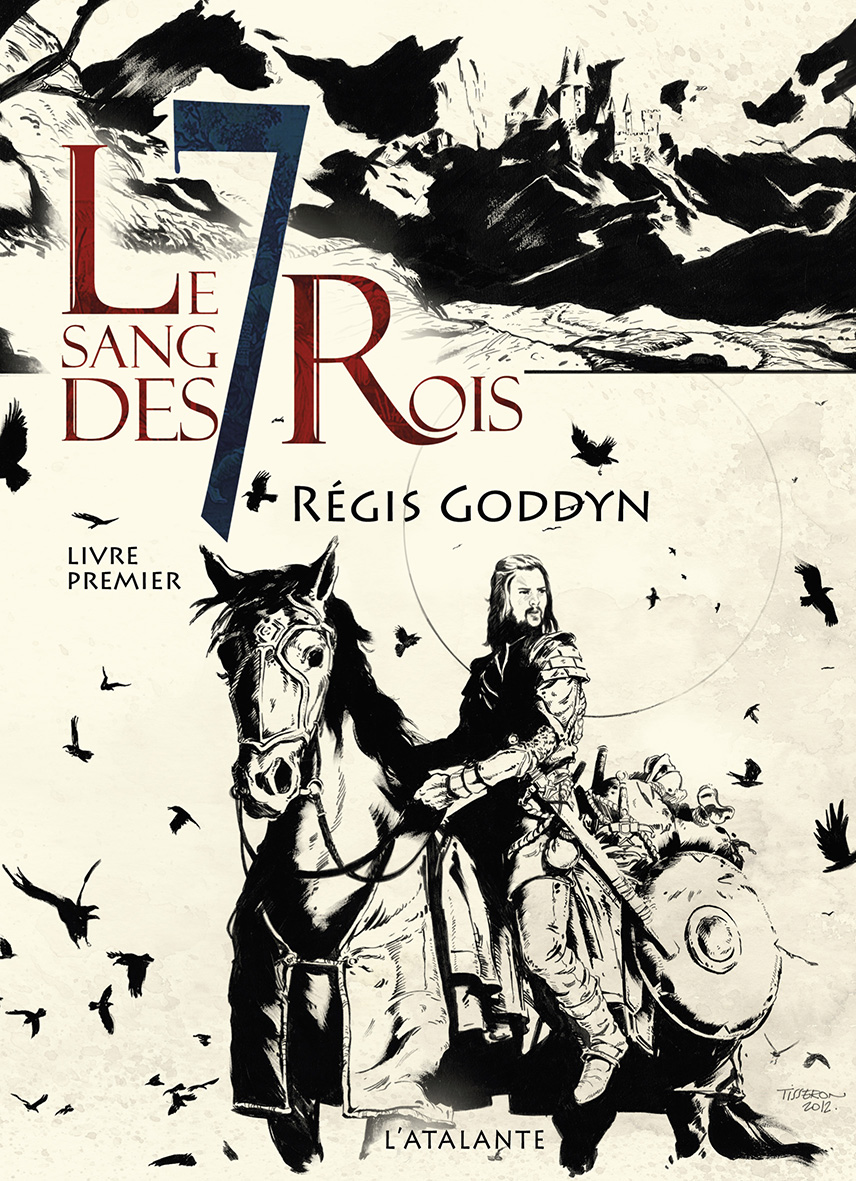

Le Sang des 7 Rois (The Blood of the Seven Kings)

“Pétrus took his lute and strummed a few dramatic chords. He cleared his throat.

— Hear ye, hear ye, good folk! On this beautiful spring day, I will tell you the true story of the Captain of the Rocks, Lord of the Gulls, Highness of a fort lost in the midst of the raging waves, Emperor of the Storms and Clouds so eager to go to the fertile lands of the Seven Kingdoms to mourn the desolation of these remote places. I will sing to the glory of the bushes, the pebbles and the winds; to the glory of women, of the most beautiful children; to the glory of our lost loves, our ravishing dreams, our ravished futures.”

On a remoted planet in the Solar System, Sergeant Orville lives a quiet life on the sentry walk of a fortress that no enemy ever attacks. However, his peaceful existence is disrupted by the abduction of two ordinary teenagers. On behalf of the King, Orville tracks down the abductors, setting out on the paths that lead to the Ridge, a giant mountain that is said to be impassable.

The event that threw Orville on the road shakes the medieval world and tears it apart. At the heart of the tensions, children are born at random with blue blood, a heritage of ancient Mage Kings that allows them to enjoy great strength and longevity. Aware of the dangers that these individuals represent for the already fragile political balance, the Inquisition conducts a relentless culling of the population, with many being executed at the stake.

Secret societies clash, political balances are disrupted, pirates prowl and live on plunder while enjoying the benefits of complicity... Yet the real danger comes from elsewhere: a magnate from Earth has targeted this isolated planet to retrieve a code he has been deprived of, and which would grant him immortality.

Press

“With The Blood of the Seven Kings, Régis Goddyn signs andambitious and well-crafted first cycle which offers a very innovative story at the crossroads of genres. He demonstrates that the French science fiction knows how to renew itself with talent.”

Fantasy à la carte

Book One

by Régis Goddyn

L'Atalante, 2013

The man who meditates not, lives in blindness;

the man who meditates, lives in darkness.

The choice between darkness and darkness - that is all we have.

Victor Hugo, William Shakespeare, 1864

"We always have the choice, we're the sum of all our choices."

Joseph O'Connor, Desperado, 1994

Chapter One

"Hey there, is anyone coming?"

Leo heard the shouts, and drew near the battlement to see who was drumming on the gate this late. It was the end of Leo's night watch. It had been rainy, and it must be close to the hour when his relief would send him back to the guardroom to sleep. He was weary, soaked and in a state of torpor. Since that last wound at the battle of Croche Pass, years ago, Leo had trouble sleeping at all. The slash had healed and the pain departed, but weird sensations prickled and murmured incessantly in his half-benumbed leg. Before, he could flop down on his mats and sleep until morning in total repose. Now he had to lie down slowly, carefully, and stuff straw under the canvas to prop his legs and arms - not too straight, not too bent - just to find a position to sleep. Then, after lying down, the vertebrae at his lower back felt like they were splitting apart. He had to wait for his body to settle down. The memories flooded in, rancor and rages of the past, and sleep fled away. And this last wound only hid the worst affliction of all, the one that never heals and that you never want to think about: Leo had gotten old. He leaned over the parapet, trying to pierce the black ink of the night.

"Step back, friend, so I can see you!"

A dark shape moved away abruptly from the precarious refuge of the projecting stone wall. Leo lowered an oil lamp suspended from a chain, lighting the mist with its trembling halo. The man pulled his hood back. He was about fifty, and what Leo could see of his hair was gray. Leo recognized the man from the long slash across his right cheek, cutting it in two. He knew old Traban, though they had never been close. The peasant had fought in the ranks when their Lord fought against Banstrom at the Battle of the Ford. As always, to obtain the numbers needed, they'd had to expand the rank and file, so all peasants capable of bearing arms had been gathered and given weapons and a bit of rudimentary training, to hold their own as well as they could. Men who had been cutting wood and working the fields the day before... He'd heard about the battle, if you could qualify a local skirmish as such. No more than one hundred and fifty combatants from around the area, two-thirds of whom were peasants half-dead from fear. Their motley assortment of weapons, hastily-patched relics of war for the most part, gave the marching troops the air of a carnival, rusty and jangling. Pieces of armor, which had already proven inadequate in serving their defunct owners, mixed pell-mell with rapiers of all shapes and sizes that no peasant knew how to use, and maces and flails that risked wounding the men carrying them more than their enemies. They were just peasants... As soon as battle was engaged, an indescribable melee erupted, a hopeless butchery that later offered the crows a superb feast. Any trained soldiers in the ranks, on both sides, had done rather well of it. Intuitively recognizing each other, the two factions' career soldiers had avoided dueling and instead, had decimated their adversary's peasant-soldiers, as if determined to destroy each other's economy. Nothing like the great battles that Leo had fought, when the king went off to war and commanded his vassals himself.

The peasant Traban hadn't made out too badly, though. He had survived, to return to a village nearly emptied of men and in consequence, no shortage of land or women. He'd had to work hard, like everyone here, to feed so many mouths with so few men. His Lord had rewarded him with a woman and the rights to a small piece of land on the heights, bordering the Bout Forest. A fine situation with a stream and virgin forest. A windfall for a boy of fourteen, who, thanks to the dearth of men to fill the role, was promoted to the rank of adult male. The old story, that of every generation of the village folk.

His wife had soon died, leaving him a son, who in turn had died after giving him his first heir, a girl. So Traban lived up on the mountain with his daughter-in-law and the girl, awaiting the day he would leave her his property, when his time had come, and when she had reached the age to marry.

Leo saw Traban from time to time at the Sunday market. Nothing more, yet the man with the face sliced down to the bone impressed him, he didn't know why.

"What brings you on horseback this accursed night, Traban? Can't it wait ‘til tomorrow?"

The old peasant answered with the strangled, high voice of someone trying to look straight up.

"It's my granddaughter. Soldiers have carried her off. I ran after them, but couldn't go fast enough, so I've come to ask for his Lordship's help."

"Let's not talk about it under this pouring rain. Come in under a dry roof and tell us all about it."

Leo went down to open the gate.

*

"What were they like, these soldiers?"

The interview took place in the castle's main hall, where the Viscount de Hautterre dispensed justice. He also ate there, received visitors and even slept there when the night was too advanced and empty tankards spoke of the next day's nausea. That was not a very frequent event. The hall took up the ground floor of the residence next to the curtain wall. It was a rectangular room, and compared to the low-ceilinged, smoke-filled peasant farmhouses, it was of vast dimensions. The furnishings were luxurious. A huge rectangular table was fashioned from heavy, thick slabs of wood. Iron chests placed against the walls served as seats when pulled up along the sides of the table. Nobody knew what treasures they held, or had held since the era when the present Lord's grandfather had started building the new fortress. All they knew was that the construction work had slowed down during the last several years, and that the few remaining workers had little money to spend at the village inn. The chamber's half-timbered walls were filled in with a mixture of earth and straw, and freshly limed. You reached the second floor via an exterior staircase that climbed up the façade to a covered porch. From the courtyard, you could see a door there ornamented with crude wrought-iron designs. It opened onto the living quarters, a series of rooms communicating with each other, and lit by windows furnished with shutters. The single-sloped roof, made of flat stones, abutted to the curtain wall. To prevent fires in case of attack, the traditional roof thatching had been excluded. Even the placement of the castle had been chosen with great care. The ground was firm and hard, secure against undermining.

The castle occupied a rocky space overlooking the river far below. On that side, cliffs blocked any access and protected them from attack. Fortification efforts had therefore been concentrated on the other side. A ditch had been dug, and studded with pikes to defend the walls. You entered the interior courtyard by a bridge without parapets, defended by two rock-solid towers pierced with arrow loops. Three sides of the castle were rectilinear. The fourth followed the curves of the cliff so closely that a man on foot could not walk between the wall and the void. From below, this gave the austere edifice an air of breathtaking fantasy, like a heavy drapery made of stone, contradicting with a certain irony its purely defensive function. Towers at each angle completed the defenses, and a wall-walk permitted circulation around the perimeter of the fortifications. The donjon was under construction on the west side of the courtyard. From the break of dawn, you could hear stonemasons making their tools sing out on the hard stone, stone that was hewed out of the mountainside by quarry workers, rugged men of few words. The castle enjoyed a breathtaking view of the ford, which remained the only simple way to reach the hanging valley constituting the domain. From the river, a stone-paved road snaked its way up the narrow valley. The first Viscount of Hautterre had erected a small fort in a bottleneck of the valley to protect the entrance to his fief with only a handful of men, because back then, the domain counted no more than that. Once completed, the castle and its menacing gray mass would replace this garrison and dominate the access road to the valley.

Edmond de Hautterre, the third to carry the name, was the very image of a viscount. Not very cultivated, not very curious, and he had no imagination. He devoted himself chiefly to managing his domain. The task proved simple. A few villages, a few hundred peasants and artisans, an isolated, poor but peaceful viscountcy. It was, however, the center of his world and nothing but imperial orders could have made him leave Hautterre. He was tall in stature, wide of shoulders, sparing with his words and moderate in his judgments, nonetheless, the Viscount had the reputation of being a hard man, built in the image of his mountains. He knew his people, and the occasions in which he needed to exercise his powers were proportional to the size of his fiefdom. Nothing indicated that he would be capable of more. A viscount...

Traban kneeled before his lord, with his eyes lowered.

"They were bigger than me, and stronger," he said in a faint voice. "I tried to fight them off, but they were stronger than oaks."

"What kind of arms did they carry?"

"I saw no arms, Your Lordship. They wore armor, black armor covered with cloth."

"In cloth? Armor covered in cloth..."

Edmond de Hautterre could not grasp, this early in the morning, why soldiers without arms but wearing coats of mail covered with cloth would be interested in a peasant girl. Many of the details described by the old man jarred with the idea he had of his world. Soldiers are armed, always. If these were mercenaries, and if they were in on the abduction, the package would have to represent a goodly sum to balance the risk of the gibbet or the blade. Plus, a mercenary leaves no witnesses, and a mercenary has an employer. Now what employer would risk even a single denier for a peasant's daughter?

"Did they say anything?" he asked the man.

"Nothing, my lord, not a word. Hardly a minute passed, before they'd left with my grand-daughter screaming over their shoulders. I ran after them, but they ran as fast as horses. The longer they ran, the farther ahead they got..."

"And your daughter-in-law?"

"Untouched. I left her with Cardhus' widow in the village. She saddled a horse for me, and I came as fast as I could. They took her son too."

Two children now. How many would there be by the end of this story? Hautterre felt the anger rising in him bit by bit. Events like this had never occurred in the valley, but wandering soldiers could have noticed the isolated farm and decided to make the most of it. In that case, someone would have found the old man with his throat cut, the daughter-in-law raped and the girl beaten to death, or the contrary.

A few chickens had disappeared, nothing more. And how could they run with armor? None of it made sense.

"You say you ran after them. What direction did they go?"

"They went down toward the Sawmill Road, My Lord."

The viscount reflected a moment. So they had cut across through the Roches Woods, then climbed back up in the direction of the mountains.

"Can you tell me where that road leads?"

"Nowhere, My Lord.... It doesn't lead anywhere."

The man started to lose his composure, and his voice became weaker as he realized they didn't believe him. His story might ring false, but tonight all he cared about had been torn from him. Why did it have to be his grand-daughter?

"Your Lordship, please send a few soldiers to follow their traces. If they don't confirm my story, I will enter your service. In any case, I no longer have the little one to pass my lands on to, so I'm good for nothing more..."

Edmond de Hautterre did not know what to think. It would seem to be nothing but a fable, but on the other hand, a peasant could not have completely invented a story like that. Or else.... A memory arose, like the shadow of a passing cloud in the middle of a hot summer day makes winter surge up, just the instant of a shiver.

"Leo, tell Orville to go with a patrol to verify his tale."

He turned back to the peasant.

"Grandfather, you will accompany the guards back to your farm. If you can't keep to the saddle, you can run behind your mount. If you've invented all this, it will cost you for having troubled me. You may go now!"

Leo and the old man left the main hall by a double-winged door opening onto the courtyard. About fifty steps sufficed to reach the guardroom.

"Wait for me here. I'll come back."

Leo went up a spiral staircase made of stone, pushing himself up with his hand on the exterior wall on the left. He entered a vaulted room where a dozen guards sat eating. The room was heated by a great chimney, where, night and day, a cauldron simmered on a slow fire. He served himself some stew, then sat down heavily, and as he plunged his spoon into his bowl, he addressed the sergeant facing him.

"You've got work today, young peacock!"

Leo and the sergeant Orville were fond of each other. They weren't the same age, nor did they share the same experiences, but they often trained together. They shared the same combat discipline and the same manner of baffling adversaries with nonacademic, rather dubious slum tactics. Perhaps in a livelier, more urban context, the two men would have passed each other without a glance. But in Hautterre you so quickly noticed the differences between you and all the others, that any points in common quickly rose above first appearances. The two men had become such good friends that not one day passed without their getting together to play dice, share a jug or talk in front of the fire in the guardroom. Orville was a fairly tall man with long blond hair that hung down over his shoulders, in the style of warriors at that time, and his skin looked pale, after a winter without much sunshine. An even-whiter scar, just visible, traced a line across his chin.

His muscled, vigorous arms terminated in large hands roughened by the daily handling of weapons. Wide shoulders served as a frame to a face whose fine features were somewhat coarsened by an overly-rich diet. The cold of winter thins down peasants but it fattens up soldiers. Patrolling was reduced to a minimum in this dead-end land, where nothing ever happened, and the guards' sedentary life dulled their spirits at the same time it bloated their bodies.

Orville did get some exercise as master of arms, but with no need for an elite corps to defend anything whatsoever, he was not very inspired, and each day inevitably ended in front of a mug of beer and plate of meat. For all that, Orville passed for a fine blade, an agile, powerful man whose tranquil friendliness went hand in hand with a promise of danger. An archetype of the warrior paradox.

"Let's hear it, old lady!"

Leo smiled at the insult and sat up.

"Traban, the old farmer from up the mountain, in the woods, the one with his face sliced in two, he came this morning. He says someone's carried off his granddaughter as well as Cardhus' son. The viscount wants you to look into it with your patrol. Report before this evening."

"Wine of the gods, a turn in the hills! With news like that, you're always welcome, Leo!"

He turned towards the men at table.

"Sirs, we're going to get some fresh air today!"

He got up with some difficulty from the bench, which was always too close to the table for a man of his size, and strode out, followed by a half-dozen soldiers.

Leo looked up from his bowl of soup to yell after them, "The old man hasn't slept, he's wet through, and he won't last the day out if you make him run. Take it slowly, Orville!"

The sergeant was already heading down the stairway at a dogtrot.

*

The patrol had been walking steadily for a good two hours. Sergeant Orville had first stopped in the village to take the deposition of Cardhus, who kept the inn there. Her husband had died of the plague three years previously. When news of the epidemic had reached Hautterre, the gates to the valley had been closed, like every time danger threatened. Isolation could be a chance to survive. But to keep his business alive, old Cardhus went out every week to buy provisions and bring goods back to the postern. He left cases and casks not far from the old fort and picked up the pouch of money they had put there right in view of the road for his attention. He looked after the soldiers' welfare, risking his life to see what he could still find in the chaos of the external world, to improve the recluse life of the valley. Times of plague were propitious for his affairs. Not that food was easy to find in these troubled periods, but widespread disorganization eased the mobility of riches. Domestics profited from the disarray of their masters, whose families were thinning out, to lift easily-negotiable objects from their rooms and finance their own flight. Their bodies were generally found at the roadside, robbed by some gang that one day would swing on the end of a rope. Thus fall out men and all things. Cardhus was not necessarily brave, nor did he particularly enjoy frequenting the sick and dying, but he couldn't make a living from his village inn alone. One day, he didn't come back. Madam the widow Jasmine Cardhus and her son lived from then on without luxuries, but without lacking anything either, for Cardhus' disappearance lightened the load of feeding three mouths when the work of the inn required no more than four arms. Their inn, also the only shop in the village, was now provisioned by peddlers on fine days, once the access road to the suspended valley was cleared of snow.

Widow Cardhus had told Sergeant Orville that old Traban had hammered at the door in the middle of the night. After bringing the daughter-in-law in, Cardhus had gone to awaken her son to go saddle the horse; the castle was still far off and the old man seemed exhausted. But her son was not upstairs or at the stables. At first she'd thought, with a smile on her face, that they were both in on it, and that a new generation was stirring in the entrails of her boy. He'd been grouchy for some time. The more hairs on the upper lip, the more hostile the cock's crow, she thought. But when went back down to the stables, she had noticed some strange footprints on the ground, clearly outlined in the pale light of the sliver of moon you could just see between clouds. Normally, any tracks on the ground led from the stairs to the kitchen, and were few in number. She had then followed the path that led into the mud of the courtyard, then toward the road. Too many tracks for one child, leading at first in one direction, then in the other. The feet were too large and the stride too long. Orville was not a bad tracker and the beer Cardhus had given him had put him in excellent humor. The previous night's rain would make the path easy to follow, as long as the tracks did not head to the stone-paved road.

Orville was the third son of a count on the kingdom's northern frontier, destined from birth for the exercise of arms, which was a good thing for him, who had always had a taste for intellectual and spiritual matters...as long as they concerned good living and satisfied the basic senses of an honest man. When a mere boy, he showed a highly developed disposition for street fighting and smooching with scullery maids. But no one had counted on the untimely disappearance of his younger brother, who one day did not come home from the monastery where he studied to become a theocrat. The plague had cut his life short, and Orville had to renounce his military career and take up his brother's, in the service of the Supreme. But after seven years of studying the Holy Scriptures at Folcross Monastery, he'd escaped the theocrat sentries to run the streets and embrace life. From the age of sixteen he had moved ceaselessly, working at a dozen different trades and living under false names. One day, a city sergeant noted his vigor during an especially fierce fight, and without ceremony, had him seized. A month later, Orville was a simple soldier in the ranks of a town Master. He had sold his liberty to escape the gallows. He would have the life he'd always wanted, the life of a roughneck soldier.

This mission being his first distraction in months, Orville took it to heart. Plus, it would help him into the good graces of Cardhus and Traban's daughter-in-law. It was sad to see those poor women sobbing for two good-for-nothings out on a stroll.

He and his guards had lost the trail on the stone paving, so they were now headed to the old man's farm. The path barely allowed passage of one horse at a time. The venture was getting interesting. One runaway lamb might lead to a whole herd playing in the woods. Three or four men, no more, had entered and left Cardhus' inn, and if these bumpkins had taken the Sawtooth road, Orville knew they couldn't get very far. That valley led to a larch forest where a lumberman's camp had been set up. The lumber no longer served for construction, for the village had finished growing too soon. So they sold it to the neighboring burgs in the good old days. Once their freight unloaded, the wagons would bring back grain or other produce that the few tillable fields in the domain could not grow in sufficient quantity to keep everyone's bellies filled through the winter. At worst, a search across that zone would allow Orville to clear up this affair and bring back some game for the viscount's table.

They left the field lanes and started up a rocky footpath. Thorn bushes on each side, cut to a man's height, forced the horsemen to dismount. They continued their climb up, widening the way with strokes of their swords so the horses could pass without hurt. Two leagues farther on, the path came out onto a clearing, where vegetables were growing. Traban's home was built on a slight elevation above the garden, but it was so small and low it seemed to huddle down, and its position against the flank of the mountain made it seem even more modest. Its entire back length was buried in the hillside; you could climb onto the roof without a ladder if you had a mind to. As for the façade, it was about the height of a man, with no opening but a plain door. The thatched roof had suffered the ravages of winter, but the cleared areas showed that the master of the place worked to maintain his holdings. A few feet to the right of the cottage stood a small building that harbored a bread oven, judging from the stone chimney and the curves of one of the walls. On the lower ground, a stream flowed past, completing the rustic, peaceful setting. Everything Orville detested. Give me a tavern, he thought, with women and some strong, freshly-distilled alcohol to chase away the winter chill...

They attached the horses to the trees nearby and the sergeant approached the door. What remained of it was solid wood, not at all worm-eaten, yet it had been broken under the impact of a violent shock. A boot? No, maybe a boot would not have sufficed. He lowered his gaze, looked at his own boots and reasoned that whatever had given the blow could not have been a boot. He looked mechanically around for what could have been used as a ram, but discovered nothing. The door, ripped off its hinges, seemed to be folded in two. He entered the room and closed his eyes to adjust to the obscurity more quickly. At first glance, nothing else seemed to be damaged. A rough table with a well-worn top occupied the center of the room and tree stumps around it served as seats. A fireplace that must have usually heated the house was now cold. The worn, pitted look of its hearth spoke of the rigor of the climate in these godforsaken mountains. Even during days of great heat, the night's biting cold chased you into the most sheltered nook of your lodgings. Orville, who had passed his childhood at an altitude where winter was more clement, had quickly discovered that the braziers placed around the guard-walk at Hautterre weren't at all an extravagance during the hardest cold periods.

Orville had begun his military career in the mild climate of a western city, and his profession had opened doors and filled mugs. Open your eyes to who was approaching the city, close your eyes to what goes on in the slummier parts. Two visions that had in fact nothing contradictory about them. It was a question of focus. He saw clearly that his debauched life would have continued unchanged until plague, a misguided blow, or the denunciation of a jealous husband would find him in close accounting with the Supreme...

While he explored the room, he kept thinking about that cursed day when his town master had lost more than usual at betting games, and had been forced to let the victor choose among his possessions to clear his debt. Hautterre had not wanted gold or grain. Instead he'd left with the burgomaster's three servants in tow, including a young, robust soldier, himself, Orville, and a great disservice it had been to him.

In a city, people are always passing through, and the population concentrates and renovates itself. In isolated regions, men equate riches. In real dead-end places like the viscountcy of Hautterre, only someone with a sincere interest comes, and only someone with no other choice stays. It wasn't until reaching the end of the road into Hautterre that Orville realized his life was ruined. Goodbye beer, goodbye redheads, blondes, brunettes and feasts every payday.

His eyes were getting used to the penumbra and details grew visible even in the dark corners. The rush mats were clean, and only the smashed door showed that something out of the ordinary had occurred. He tried to imagine the scene as the old man had described it during their climb up. Everyone was sleeping. The woman and the girl on the large rush mat, the old man on the other mat. Suddenly (Orville swung around), the door flew into pieces under the blows of... he didn't know what. However! He turned back to face the rush mats again and visualized their occupants sitting up horrified. Without a word, the soldiers, if they were indeed soldiers, had headed toward the girl's mat. Orville walked over to it and leaned over as if to seize her, closing his grip on an imaginary child, when his hand struck something in the straw. He grasped a small leather pouch, quite ordinary-looking, closed with a simple lace. To get a bit more light, he went back to the middle of the room, contemplating it, then untied the cord and poured a dozen gold coins into his hand. An inconceivable fortune for a peasant. He approached the door to examine them in the sunshine. When he was a sergeant in the city he had seen all kinds of coins. It was rare to see gold ones, naturally, but he could boast of possessing a bit of experience in the matter. These coins were perfectly unknown to him. A half-inch in diameter, one face carried a rather banal crest barred diagonally with an arrow, and the other face had a five-pointed star ornamented with a little circle in the center. A strange find. Orville pocketed the pouch.

He would evidently find nothing else in the shack. He went down to quench his thirst in the stream before going back to question Traban again.

"What direction did they go?"

The query was purely for form's sake. He would have to be blind not to see the footprints in the dirt heading west to cut across the woods. At a vague gesture from the old man, the sergeant advanced in that direction. On reaching the thickets, Orville spotted the trail going up a steep, pebbly slope. He reflected an instant and then addressed two of his men.

"The horses can't pass this way! Go back down by the path with the mounts, then take the Sawtooth road at the fork. You can meet up with us there. You others come with me. We'll follow them on foot. A little stroll, gentlemen!"

He turned to the farmer.

"So, it's up to us now. Go back to your daughter-in-law, and news shouldn't be long in arriving."

He gave Traban a little push, and then headed across the bush, on the tracks of the aggressors. The brambles soon gave way to a freshly-cleared path, one of those mountain paths invaded by brush, that long ago led to some far-off slope of tillable dirt. In times past, every bit of exploitable land had been planted with food crops, no matter how distant from the village. Now, wagons came up with supplies to replenish people's pantries, and these paths had returned to nature, and gradually slipped out of memory. Steps were cut into the slopes at irregular intervals, ditches had been dug to prevent rainwater from sweeping away the humus and the stonework of the path. The patrol had been hiking about half an hour when Orville noticed something that had been glaring right at him for some time.

Why had a path that supposedly led nowhere been re-opened?

He imagined the three kidnappers in their cloth-covered armor, pushing through brambles in the deep darkness of the forest at night, then breaking into a run on this forgotten (but cleared and leveled) path, with two kids bawling like lost calves carelessly tossed over their shoulders. Assuredly a nice piece of work. But why? And why this fortune in gold posed on the bed of straw? It hadn't fallen by chance. At the head of a commando like that, he wouldn't have gone to so much trouble. His thoughts led him back to this implausible trail, in bush thicker than any they'd had to cross since leaving the cottage. The men who had traveled it the night before hadn't cleared it along the way, plus they'd left the first dozen yards of the trail in its natural state, probably so that it would remain invisible until they needed to use it. The brush here seemed to have been stamped down rather than slashed aside with a billhook machete. The branches were turned back without having been sliced, as if swept back by a cavalry charge. The prints headed toward the woodcutters' camp, at the right, conformingto the old man's story. The night's rain having washed down the tracks here on stony ground, Orville decided to go back down the trail to search for possible detours to the left or right. They hiked another solid hour before meeting up with the men in charge of the horses.

The Sawtooth camp was no more than a quarter of a league off when they detected a fresh path plunging into the woods on the right, in the direction of a rift named Goat Ravine. This path was known to all. Once or twice a year, the peasants led their flocks there to graze the bit of grass that could be found. The passageway, with its vertical walls, opened onto a rocky, bowl-shaped area of sandy soil, where the cliffs rose up over three hundred feet high. The spot was majestic, but Orville thought that if he were fleeing with hostages, he wouldn't choose that dead-end as a destination. About an hour after leaving the Sawtooth road, the humid and odoriferous soil of the underbrush gave way to a rock-strewn footpath in a patchy forest. The gravel rolled under the iron of the horse's hooves and frightened birds, which flew down from the heights in a great ruckus of wings. Sergeant Orville worried that all the noise would alert the raiders, but not being able to control the creatures of the air, he resolved to follow as silently as possible. A little farther on, the path swung around a huge boulder arresting the course of a torrent and creating a ford. Orville dismounted to examine the tracks more closely, at the point where the rocky path gave way to a wide beach of silt. The footsteps were no longer the same as those he'd noticed during the hike down, or rather, they were the same but more numerous, of five or six men perhaps, and the prints showed that two mules now accompanied them. He ordered a halt to rest the men and let the horses drink, then sat down on a flat rock off to the side. The scenario was taking shape in his mind: two commandos of three or four men, one in the village, one at the farm. Rapid action in the middle of the night, but no violence. A purse left in the very spot where the girl abducted from the old man's home had been sleeping. Was there also a purse on the Cardhus boy's bed? Orville had not inspected his bedroom. Days of preparation to clear the trails, to find mules. Where had they found them anyway, in this country forgotten even by the Supreme? The question of accomplices would have to be posed later. And now a meeting of the two commandos with the two children, whose role was still a mystery, moreover, and the whole lot end up walking through the woods into a dead end. There must be other possibilities he hadn't yet imagined. Maybe he was on a false lead, and the attackers were heading toward the village of Rueil. Or did this way lead to another forgotten path and some unknown pass into the high alpine pastures?

They continued until midday before having to dismount and take to their feet again. They had to enter the narrow defile now, where horses could not pass, so they tied them to the low branches of some trees near the trail. The prints were fresh. Every sense alerted, the soldiers advanced step by step for an hour, when the smell of smoke stopped them. Smoke, but also smoked meat. Seized with a sinister premonition of the nature of the venison, Orville slipped between the trees, sword in hand, until he could glimpse a clearing encircled by boulders. Obeying a gesture of his hand, two of his men glided between the boulders to left and right, bows at the ready, while he edged toward the opening, watchful, his heart beating hard. Under the cover of bushes, he approached close enough to see that the clearing was empty. They had eaten there. Men had sat around the fire, and he saw footprints smaller than the others, confirming that the children were still alive. A deer carcass was blackening to cinders on the fire, perfuming the air with rare spices and charcoal. A cask of wine half-full lay on the ground near the fire, tempting, incongruous. A little farther, two picketed mules waited for someone to take charge of them. But why were they picketed? Were these commandos so sure they would be followed, and that their pursuers would arrive here to take care of the animals? Had they left the camp in a hurry, detecting their approach? Orville was following the prints up the path when he saw two arrows stuck in the ground, two black arrows with feathers of blue, crossed to form an "X." He pulled them out and examined them. They were well-crafted, straight, although a bit long, with mortal steel points forged with precision. He took a few more steps, then suddenly another arrow flashed into view and pierced the ground at his feet with a solid thump. He leaped aside, rolled onto his shoulder and came up behind the closest tree before risking a glance in the direction it came from. He saw nothing but a chaos of tower-like rocks, each of which could shelter ten archers, or one, or none at all. Their pursuit was over.

The enemy was at bay in the defile, and Orville was blocking its exit, but he could do nothing more without risking his skin. If he left, the assailants would escape, and if he advanced, they would be massacred. Each rock constituted an impregnable fortress giving the entrenched archers capital advantage over Orville and his men, who had to advance in the open. If he launched an assault and died with all his men, the road would be clear for the fugitives, and they could take off at will.

Thus, the situation was at a standstill, but he was still the one who controlled events. He addressed one of the soldiers, one he knew to be a good rider.

"Iban, take the horses down to his Lordship and tell him where we are and what the situation is. You can explain how urgent it is that he go immediately, and in person, to inspect very closely the Cardhus boy's room. Make sure no one enters it before his arrival. Do you understand?"

The soldier bowed. "Yes, Sergeant!"

The message was enigmatic, but to say any more would lead to mention of the purse, and to avoid the risk of losing invaluable evidence he had to be prudent. After the messenger had left, Orville organized his defense of the ravine entrance to consolidate their hold on that key position. Why here precisely? Why had they prepared this kidnapping so methodically, to end up in the sole gorge accessible to the domain but without another exit?

The messenger, Iban, rapidly climbed down to where the horses were attached. When he reached them, two were missing.

The night was long. The fire was kept burning and the watch succeeded one after another in the expectation that an enemy could attack at any moment. Orville sent the soldier Miller to requisition food from the first farm along the road to the village, and he came back three hours later with a chicken, half a loaf of bread and a gourd of bad wine. At least, keeping watch on this crazy ravine was a change of scenery for Orville. The Hautterre castle was on a foothill of the mountains, and on a clear day, from its ramparts he could see the plain stretched out enticingly before him, with its big towns full of life and new encounters. A pox upon dice!

Watching and waiting had become second nature to him. However, if these redoubtable warriors appeared in the middle of the night, protected by their armor and a few formidable swords, he wouldn't regret the gourd of wine he had drunk freely of this night. In any case, there hadn't been enough for five men.

Their reinforcements arrived about an hour after sunrise. Twelve heavily-armed men, who were all the more welcome, seeing as they had brought rations with them.

"Hello there, Orville! So what have you caught up here in Goat's Ravine?"

Leo dropped his bags and grinned as he rubbed his lower back. Orville stretched, embraced him and responded with a giant's yawn.

"Hello, old friend. I don't really know yet. The two kids are in the ravine with six of those dogs. If you go past those crossed arrows over there, you receive a volley. Even at night. I tried twice, and nothing doing. You go too far and the bowstring snaps."

Orville joined a gesture to his words, miming an archer letting fly an arrow.

"That sounds bad, Orville, in my opinion. Anyway, we've come ahead of the main group. Others will join later. We should be about fifty all together, and there's better."

"Women? Yes!"

"I'll say nothing, and let it be a surprise. I'm not sure what's going on, to engage such a large detachment. There must not be many left at the castle."

"True. Fifty, you say?"

"Plus, some surprises. You won't believe your eyes. Get some rest. The day is not over."

The two men exchanged a friendly smile, and some of the new men having taken position, Orville went off to curl up behind a boulder, sheltered from the wind. He'd slept only a few hours before a man came and shook him awake. A bit groggily, he made his way back down to the camp to welcome the rest of the troops. He was about to give the order to deploy when he noticed among the advance party of soldiers the bluish armor of Edmond de Hautterre, and just behind him rode Theod, the domain's theocrat, wrapped in his purple cape belted with a black cord. Orville had an aversion for this man, for he instinctively distrusted those who had none of those solid defects that make characters and men. Theod, most likely the second son of a minor aristocrat, was an ascetic, discreet man, smooth and sharp as a dress sword, but too precious to confront true life. Theod acquitted his office with a zeal that the sergeant scorned, and to his eyes, Theod represented the specter of what he himself might have become. Orville mustered as confident an air as he could, then went forward to meet them and drop to one knee before his protector.

"You may stand, Sergeant. How did you know about the pieces of silver?"

Orville pulled the pouch from his pocket and handed it over.

"Twelve coins were on the girl's mat, but of gold, my lord, not of silver. For the Cardhus child, it was but a guess."

"Of gold!"

Orville felt the viscount's stupefaction, which took several long seconds to overcome. He then said, "Sergeant, have Leo called, and then rejoin us!"

With his hands crossed behind his back, Hautterre headed over to the fire, where sausages were grilling. The theocrat followed him like his shadow, even to wearing the same worried look.

Leo was Hautterre's most experienced soldier. In truth, he was one of the only men who'd seen service outside the valley, one of the few who'd been in combat and come away with his life. All the others of his generation had died in combat or of illness. He was a free man, a mercenary whose contract Hautterre had paid out. He had entered the service of the family a few years previously and would probably finish his days on the castle keep, with his eyes fixed on the distance and his feet in the snow. His situation and Orville's hardly differed in the details, except that Leo had the comfort of knowing that at any moment he could pocket his pay and take to the road with his sword and helmet. Even at his age...

Hautterre was in the habit of consulting his men but then doing as he wished. A manner of consolidating his impressions, whether the advice converged with his opinion or not.

"Leo, what do you think of the situation?"

"Your Lordship, it's not at all logical when we look at it from our point of view, but those men don't share our view. We must think like them."

"Explain yourself!" Hautterre said as he threw a branch into the fire.

"Well, the enemy prepares everything meticulously. They clear the trail, bring up mules before the winter, and then go precisely to a place they cantt escape from."

"And why would they do that?"

"I would say it's to draw us here. I don't think they're trapped -- they're patiently waiting for us."

Leo's expression oscillated between concentration and amusement. Distractions were so infrequent in Hautterre that the least little thing served to let one's imagination run free.

"And to what purpose, according to you?"

"Just that, to lead us here...so that we are not someplace else."

"So that we are not where, for example?" Hautterre seemed annoyed with Leo's convolutions, for the viscount was an impatient, direct man.

"Well, we're far from everything here. It could be to get us away from the castle."

The viscount shook his head.

"There's no risk. I left twelve men at the lower fort and eight archers at the castle with Captain Whaine, and that's more than enough to hold out for days. What is the advantage of Goat Ravine? What could have made them choose this option?"

Leo did not know how to respond to that question.

"Orville?"

The sergeant, absorbed in contemplating the smoldering coals, looked up.

"It's difficult for us to follow them from this point. I tried several times, with nothing for my troubles but arrows. At every attempt. Each one of these boulders could be hiding the Supreme knows what, while we have no cover. We won't be able to climb up without an express invitation..." He suddenly interrupted himself. "Pig's blood! Pardon me, my Lord, I think I've just realized something. Now, if I knew an exit from this cul-de-sac, an exit that my pursuers didn't know about, an old footpath for example, like the one they cleared, I think I would've used the same tactic.

"It takes at least an hour to go back down to the road, and another hour to get to the Fork, and then a day to climb up to the plateau. So, if one or two archers block the entrance, and if the rest of the commando has already left, that would give them about two days advance at the start of the hunt."

"But why draw us here?" asked the viscount. "They could have just gotten away, as quickly as possible."

"Maybe that's what they did do, by leaving only a small number of men to block the ravine."

Leo spoke up then, in a serious tone. "Unless they'd wanted to rest before leaving, sheltered from the wind in the bottom of the ravine, while two of them went all the way around, with the horses they stole from us, in order to transport the children once they were up there. The fugitives could have taken off a little later by their own path, where horses couldn't have climbed."

The viscount turned to Theod. He lowered his voice in addressing him.

"I think the indications are sufficient, and it's more than time to take to the road. If things are as Leo suggests, we have nothing more to fear in going up the ravine. If we are wrong, pray for our souls."

The troops mustered again under the viscount's command and advanced prudently, following the tracks left by the attackers and minutely inspecting every boulder. It took a long time to find the archer's hideaway, but they finally discovered it, at an unbelievable distance considering the precision of the shots aimed at Orville. It was a curious setup. A platform of tree-trunks had been raised on posts sunk into the sand behind a boulder, in such a way that the top of the rock was just below eye-level. A little roof of planks protected the sentinel and a ladder gave access to this rudimentary defense post. The soldiers progressed cautiously, fearing other surprises, all the way to the back of the ravine, where it widened out into a rocky bowl with dizzyingly high walls. Rocks had tumbled down from countless slides, to form a strange decor. They looked like giant bowling balls that had come to a stop among the few trees growing out of the sand. A camp had been set up and latrines dug off to the side. Campaign tents had been erected downwind of the fire, where coals still smoldered under the carcass of a sheep. A cask of wine, half-full, lay in the exact spot where all the tracks converged at the foot of the cliff. No paths led up the cliff. The ravine was empty.

Chapter Two

Gradlyn

Aside from a few hours of rest during the darkest part of the night, the pigeon had been flying without a break for almost three days. Since his departure from the Hautterre valley, where he had spread his wings for the long voyage that would lead him to the capital and the King, he had flown over the foothills of the mountain range toward the southwest, toward the sea. He had followed the course of a torrent over to the town of Grandcerf, then along the Amir River that snaked between round, grass-covered hills. The farther his flight took him from Hautterre, the clearer his bearings became. Not that they were needed for him to find his way, as instinct, passing down through the march of the ages, infallibly told him the right direction. A sensation difficult to define to someone of another species who did not share his gift, and which he would have a hard time explaining to himself, even if he had any interest in doing so.

Woods, rivers, towns and villages paraded by below him, and the hills gave way to the fertile plains. At this late hour, men and beasts were no more than tiny points, projecting long lines of shadow on the ground toward the east. The hour of arrival was near, and he was eager to land, to feed and let his tired muscles rest. He stretched his wings out to the fullest, planing for a moment at the whim of currents wafting up from wheat fields warmed by a long sunny day. Here in the south, the climate was gentle and the vegetation rich and varied.

The voyage from Hautterre to Gradlyn was far and away the most difficult he'd ever had to fly. A steady west wind had pushed him laterally in the first part of the trip, so he'd had to make constant adjustments to his trajectory. Once out of the hills, he'd flown into the wind the whole rest of the way. He'd had to expend considerable energy to maintain his speed. Suddenly, he perceived the bright reflection of the sea straight ahead, as well as the dark mass of the city.

Gradlyn was no longer the largest city in the first kingdom, but it remained the seat of government, and it was the richest and most splendid city. Its location at the coast of the exterior ocean and at the mouth of the principle river made it a strategic point in the realm, where some regions drew their substance from mines, forests or fields, while still others relied on a particular savoir-faire in the craft of fabric or metal utensils.

The pigeon caught sight of the rock outcroppings that rose up behind the city. The mighty royal fortress was built there. His piercing vision, far better than that of men, soon allowed him to distinguish its perimeter walls, and the ships in port on each side of the wide river. Seen from the sky, Gradlyn looked like two halves of a grain of wheat, split by the watercourse. Each side of the city had its port and its fortifications, built in such a way that a flotilla trying to enter by the river would find itself caught between two fusillades. Two ferries transported men and merchandise from one bank to the other around the clock. To the north of the city, the construction of a bridge occupied masons, stonecutters and carpenters, who rivaled each other in their respective work. At his current altitude, he could hear distinctly the noise of their tools and the clamor of the end of the working day. If one took into account practical and esthetic criteria, the spot for the bridge was not well-chosen, but it did take advantage of a tiny island in the middle of the river, so there would be two shorter, successive bridges to get from one bank to the other with dry feet. The current scheme of roads and perspectives would adapt in time...

*

He flew over the port and city districts teeming with life, then passed over the inner courts of the castle, deviating slightly to the north then spinning into a dive to face the openings cut into the donjon wall. Once in the axis, he approached carefully, as he had done thousands of times, the unpredictable wind turbulence forcing him to continually adjust his position. He dove into the landing tunnel, finally ending his long and perilous voyage. The deafening noise of the wind ceased as if by magic, leaving a strange, resonating silence within him, and his entire body shivered as if he were drunk, stupefied by the wind and his efforts. He folded his wings back along his muscular gray body and remained still a few minutes, exhausted. Then a friendly hand seized him, smoothed his feathers, and detached the tiny tube of ivory attached to his foot before placing him delicately in a cage where water, grain and rest awaited him.

*

The tension was palpable in the Council Chamber of the Gradlyn royal castle. The question of the repartition of taxes collected in the name of King Hartrold IV was still not resolved, and it was the end of the day. Debates had been stormy. This year, the good harvest and a rather short storm season had permitted a surplus of commercial receipts. This was excellent news, of course, but the ministers couldn't reach agreement on the use

Germany (Cross Cult)