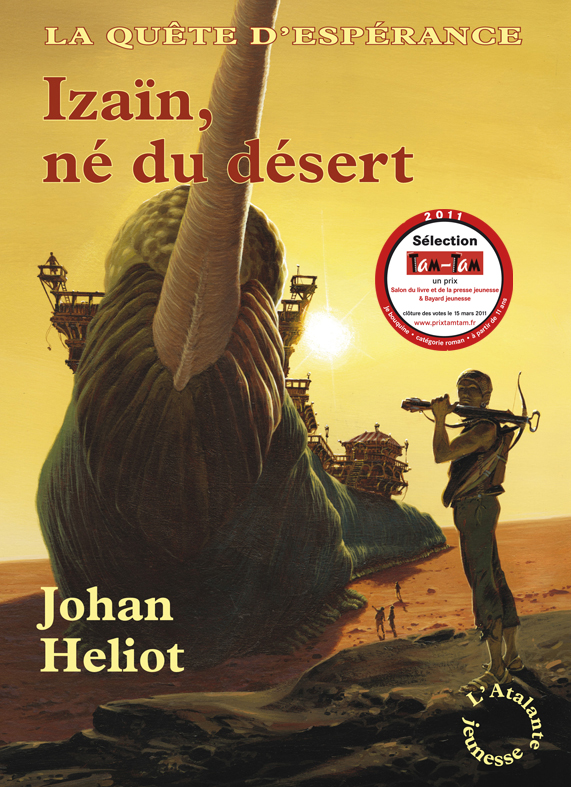

LA QUÊTE D'ESPÉRANCE [THE QUEST OF THE ESPERANCE]

Book 1: Izaïn, né du désert [Izaïn, desert-born]

With young Legyria in command, the animal vessel Esperance travels the byroads of the desert, transporting precious cargoes from oasis to oasis.

One morning, the quartermaster, Orso, a former mercenary, catches sight of clockwork vultures dancing in the sky: the frightening bird-machines are about to attack a child survivor wandering in the wake of the Esperance. Orso leaps to his rescue.

Part pirate story, part science fiction, La quête d'Espérance [The quest of the Esperance] takes the reader on a fabulous voyage, with many twists and turns, to discover a far distant world, whose origins will be revealed over the course of the three planned volumes. The Esperance, having travelled over sand, will sail the high seas and then fly through the air...

Book One

of

The Quest of the Esperance

Chapter One

The Castaway of the Desert

The boy was still holding up. For two days and now nearly two nights he had doggedly followed Esperance's wake. The boson, Orso, lay watching him from the depths of his sleeping pouch, which opened onto the stern. He was snugly installed in a layer of soft down that would be reabsorbed as soon as the temperature started to rise. Every morning, he took advantage of this brief moment of tranquility before throwing himself into a new a day of labor under the orders of captain of the Esperance. He'd had just woken up, and would soon take his watch on deck.

But before that, Orso had wanted to check and see if the boy had abandoned his struggle or not. He had to admit the kid was hanging on to life with admirable resolve. Many before him had perished in that very wake, having failed in their attempt to climb aboard. Their whitening bones would forever lie under a thick layer of red sand.

The boson could tell that this refugee, though, was determined to prevail. But from the stern, he looked neither big enough nor strong enough. But then, determination is not just a matter of muscles. Orso had had many occasions to verify that during his time serving warlords on battlefields across the whole territory. That was before he'd signed on the Esperance, tired of the combat and the blood, spilt most often for no good reason. His past life seemed like a completely different existence to him, a life lived not for himself, but for someone else, for that young and wild Orso, drunk with noise and ferocity. An Orso who would have scoffed at a sand-sailor enjoying the comfort of his feather-lined sleeping pouch!

He took his time stretching, making his joints crack and breathing in great lungfuls of the still-cool air. Then he pulled on his worn-out pants, slipped a sleeveless vest over his naked torso, and fixed a black cap atop his perfectly smooth skull. Finally, he tied a leather lanyard around his right forearm, flexing his muscles during the procedure. This done, he turned his attention back to the desert.

Far behind the child, the huge orange ball of the sun was emerging from the horizon, like a great boil bulging up out of the earth's skin. Its blood-red light shimmered in the Esperance's wake; its heat had not yet dried the rocky path, washed bare and still moist from the gastric juices the Esperance had secreted during the hour before dawn.

From the height of the stern looking back at the wake, you could easily imagine yourself on the edge of a deep canal, one dug out just that night through the dunes and the valleys of sand. Orso grimaced at the mere thought of a canal. Like all sand-sailors, he hated the aquatic environment and, even more so, the crews of men who sailed upon it.

He yawned, scratched his head where it was itching, then dug around in his sleeping pouch. He found his monocular and pushed it into his right eye. Closing his left, he searched for the figure of the shipwrecked boy among the barren dunes, which were beginning to flicker with the heat. The boson chuckled and scratched between his legs this time, vaguely thinking that the vermin aboard were starting to get a bit too free with him and that he'd have to do something about it. But all the while he was studying the boy. He could see tell what an effort it was for him to go on, crushed by the terrible rays of the sun. Rather courageous, this contender, he had to declare. But Orso had seen others. He himself had joined the crew of the Esperance in quite an odd manner... Ah, something interesting was happening!

A shadow was edging into the circle of his monocular. A vulture had evidently been biding its time waiting for that moment when its victim would have used up all his energy, but still retain a bit of flesh on his bones. Orso knew the attack would come before the third day. This was the moment of truth. They would see what the kid had in his guts, aside from his entrails, of course.

The vulture came down on the small figure with wings fully deployed. It was an ancient model, sturdy but not very reactive. Its vision apparatus must have been out of sync, because it missed its target by several feet. Its pinchers closed on the void and it clacked its beak with irritation. The kid had gotten a lucky break, but he would certainly not have such good luck at the vulture's next attempt.

The mechanical bird of prey used an ascending current of air to rise high up in the sky again. Taking advantage of this respite, the boy opened a sack he was carrying bandolier-style, and took out a thin, shiny object that Orso could not identify. The vulture had reached sufficient height for another dive. Orso's expert eye could tell it had been able to correct its error and was aiming straight at its prey this time. He was not mistaken. A clamor rose up from the Esperance's lower deck, just under his sleeping pouch, informing him that the other members of the crew were also following the unequal combat. Bets were opened. Some men encouraged the foundering boy, while others, more numerous, let fly raucous cries, imitating the rattling voice of the machine-vulture.

The second before it was about to strike, the child raised its hand, and holding the object he'd drawn from the sack, oriented it to face the rising sun. The blast of light it sent out blinded the boson. He heard the other sand-sailors exclaiming angrily. Blinking his watering eyes, he marveled at how exceptionally sharp the boy was proving. He had to be at the end of his forces and near desperation, but had still been able to come up with the idea of brandishing a mirror to blind his adversary. The vultures' ocular captors could make out the least movement for miles around, but they lost all effectiveness if exposed to powerful light. Disoriented, the mechanical bird abruptly swerved out of his trajectory. The needle-like tip of its wing raked the child's back and knocked him off balance. He fell down in the glistening path behind the vessel. Orso suddenly felt a stab of conviction that he would never get back up - not without help, in any case. And this kid had just proved that he deserved a hand!

The boson grabbed his haversack and extricated himself from his sleeping pouch. Without losing an instant, he threw himself into the webbing of the nets connecting deck to deck, and climbed up Esperance's back. It didn't take him long to reach the vessel's highest point, which was the shooting platform off the quarter-deck. The ship's perpetual, slow rolling was more pronounced here than in any other spot. But for a confirmed sand-sailor, the motion was not at all troublesome.

In one practiced gesture, Orso pulled out a crossbow from the bottom of his haversack. The stock, worn smooth with long years of use, instantly found its place along the boson's leather-bound forearm. With his free hand, he grabbed the crank, and spun it enough times to stretch the cord to its maximum. He then snapped a bolt in the notch, shouldered it and aimed, with his finger on the trigger and his breath held suspended.

A light breeze was blowing down from the interior of the land, Orso needed to plan his shot in order to hit such a remote, swiftly-moving target. But he had no time for expert calculations. He had to trust in his instinct and his experience, and above all, not look at the point of the bolt, but instead, follow the movements of the vulture, anticipate its flight by a fraction of a second, guess the moment when it would expose its rust-covered iron belly...and fire!

The shaft burst out, slicing a long rip through the air. Orso held his breath right up to the impact. The vulture did a pirouette, wildly flailing its wings, before crashing into the sand, right beside their wake. A spray of sparks gushed from its gaping beak. It would fly no longer, but decompose, buried there beneath dunes that the winds would forever shift and sculpt. Good riddance, thought the boson.

"Bang on target," a sarcastic voice announced. "Now that you've saved his life, you count on letting him die of thirst, or exhaustion?"

The sand-sailor turned toward the person talking to him. She had slipped behind him soundlessly, and stood with her hands on her hips by a hatchway opening onto her quarterdeck cabin. The breeze lifted the blond hair that hung down onto her shoulders. To Orso the young woman seemed still a child. But a child to whom he owed respect, as he had owed it to her father before her.

"Hello, Captain," he said half-heartedly.

Then, gesturing at the stranded boy, he said, "I wanted to give him his chance."

"That's generous of you, Boson."

She came up and leaned on the ship's rail close to the shooting platform. Orso watched her out of the corner of his eye. He always felt uneasy in her presence. Not just because he wasn't used to being commanded by a woman. Legyria had lawfully inherited the title of captain at Ellerios' death, being his only descendant. At that, he nothing to say. No, his uneasiness was due to the self-assurance that she showed under any and all circumstances. She was so young, but Legyria already gave the impression of having lived through too much, and of being wiser than he.

"But it appears you've decided to act too late," she took up, pointing with her index in the direction of the rising sun.

The boy still lay where he had collapsed, face down in the middle of their wake. He moaned, immobile, in the mist reddening under the fire of the sun, perfectly matched with the tint of the dunes.

"Ruddy gorchats!" cursed Orsa.

Not waiting for an order from his captain, which he knew would never come, the boson jumped over the rail. He raced across the rear deck, climbed over the rail and down the webbing of the nets, then let himself fall down to the sand, down into the ship's wake. The rest of the crew cheered and clapped.

Orso ran as fast as his legs would carry him. He knew the unwritten rules of the sand-sailor by heart. If he could not get back aboard by his own means, Legyria would not change course or halt her vessel to allow him to catch up. Luckily, Esperance was moving forward at only a moderate speed to save its energy. By now, at the tail-end of their mission, fuel reserves were down by three-fourths. But still, the boson had not a second to lose. He took great care not to slip in the slick moisture of Esperance's wake. The possibility of a new vulture attack crossed his mind. The individual he'd shot down may have had time to send out a distress signal to other creatures patrolling the sector. That was how they acted on the battle fields, after the shock of two armies meeting warrior to warrior, when it was time to clean the terrain of the cadavers and the wounded still writhing in agony. The first vulture to spot the feast contacted as many of his companions as he could, and it wasn't long before the sky grew dark with clouds far more menacing than those of a tempest...

However, Orso reached the abandoned boy without any trouble. Leaning over his body, he was relieved to discover there was still breath in him, in spite of the sad state in which he found him. His ribs stuck out under his skin, stretched with starvation. His puny limbs, half-naked under a layer of rags, looked like twigs ready to break at the least jolt. It was unbelievable he had resisted so long! Orso grabbed him around the waist and lifted him up with just one hand, the other still holding the crossbow. The kid weighed nothing. He loaded him onto his shoulder and started running back to Esperance.

The vessel had taken a fair amount of lead on him. Its massive body formed a distinct point of reference in those endless waves of sand, whose flanks the breeze was powdering with reddish foam. Sometimes, when the wind gusted up in anger, the red sand would rise up in swirling tornadoes right to the top of the sky. At those times, it was much better to seek out the shelter of a hermetic pouch than to be running across the wilderness. But any signs of an approaching sandstorm were missing. Orso feared only one thing: that his energy would run out before he had crossed the distance between them and Esperance. He cursed himself for having recklessly gone to the rescue of a half-dead creature, and he accelerated his pace until his lungs burned with fire and his heart in its thoracic cage pounded against the bars of its prison.

The encouragement of the crew soon reached his ears. The men were gathered in the webbing of the deck nets to take full advantage of the spectacle offered by their boson. Some whistled, others waved their hats. Orso could not possibly show himself to be weak in front of them. Legyria stood on the shooting platform, her arms crossed, and observed him without saying a word. As usual, it was hard to know what she was thinking. But he would show her, and the others too, what an old warrior of his mettle was capable of!

Ignoring the fist of steel compressing his chest, he called on his very last resources to lengthen his stride. He was now just a stone's throw from the vessel. Someone had thought to throw a rope out into the wake, but to grab the end of it, Orso needed a free hand. He would have to give up one of his burdens - either the kid or the crossbow. If he let fall the tiny body shoved against his neck, of course no one would blame him, except he himself. That would be like capitulating, right in sight of his goal. And the sand-sailor had never renounced anything, especially within inches of victory. So, with a feeling of death in his soul, he abandoned his beloved weapon.

An instant later, he grabbed the rope and wrapped it firmly around his leather-encased forearm. A single cry arose from the throats of the crewmembers, "Heave ho -- pull!"

They managed to lift the boson and his charge into the rear deck webbing. Still unconscious, the marooned boy passed from hand to hand before finally being deposited on the quarterdeck bridge at Legyria's feet. When Orso joined her, out of breath, with sweat pouring down his bald cranium, she did not even glance at him.

"From this day on," she said, "you're responsible for this new mouth to feed. You will have to share your rations. You know the code. Once you disembark, you can do whatever you want with him, since you own him now. But as long as he remains on board, he will submit to my authority. Is that understood, Bos'n?"

Orsa contented himself with nodding. He already regretted his heroic act. Was this kid worth the price of a good crossbow? That remained to be seen...

Chapter Two

In the Den of the Burrower

Why had he saved the boy? Orso would have had a difficult time answering that question. At least, it would have been hard to find a satisfying answer. In any case, that tomboy Legyria was right about one thing. From now on, the fate of the brat depended on him. Naturally, he could throw him back off, back into the vessel's wake, and nobody would reproach him, or he could tie him up in the depths of one of Esperance's pouches, and wait for an opportunity to sell or exchange him. On condition he recovered, that is, for the dead were worth nothing. He could also choose to train him as a new member of the crew. However, this last option would require certain sacrifices on his part that he was not at all ready to consent to...

No, finally, he was better off taking advantage of their next stop to try and get the best price. Meanwhile, Orso would have to look after his own interests. That meant getting the kid pepped up as quickly as possible. Of all the crew, only Bayu, the ship's burrower and healer, possessed such expertise. But unless Bayu saw something in it for himself, he would never lift a finger to help. Orso was going to have to do some serious negotiating with the old bat. He hoisted the small, inanimate body once again and crossed the bridge in the direction of the foc'sle. In his arms, the desert refugee weighed little more than if he had been filled with air. His canvas bag, slung across his body, bounced against his meager chest. His last real meal must have been ages ago, if indeed he had ever been able to satisfy his hunger. But it was the common lot of most of the miserable inhabitants of this region, so Orso was not going to cry over the boy's plight.

As the boson passed, the sand-sailors, hard at work, saluted him by slightly lifting the brushes they were scouring the decks with, impeccable as they already were. Legyria imposed rigorous cleanliness aboard her vessel, as much for the men as for the equipment. She was correct. Questionable hygiene attracted sickness. More than one vessel had perished due to the negligence of the crew. The structures of the bridge and rear and aft decks (or foc'sle and quarterdecks) were in direct contact with the epidermis of the vessel, rather like the shell on the backs of those sluggish, hideous beasts living along the coasts. If you let rust or fungus invade the metal or wood, you could be sure it would soon contaminate the organism supporting their weight. It was, moreover, one of Orso's roles as master of the crew to see to the scrupulous maintenance of the inorganic parts of the vessel. Its living parts were the responsibility of the burrower. Ah, but the hatchway to his quarters was closed. Was the old man still sleeping? Orso kicked with his foot against the wood panel, three times, hard enough to shake the structure.

"You needn't make all that racket," yelled someone who had just appeared at the front of the vessel. "Bayu hasn't come up from his first sampling yet."

Orso glanced up at the stem, where the prow, with its long horn of ivory, pointed forward. A frail young man with an emaciated face, dressed entirely in black, balanced at the junction of Esperance's rostrum and skull, outside the ship's rail, where nothing prevented him from falling.

The boson reluctantly acknowledged him. "Hey, Fentz."

He did not feel obliged to hide his disdain for the parasite - Fentz lived aboard, but did not really belong to the crew of sand-sailors. He did not participate in maneuvers and only rarely left the interior of the rostrum, where he had chosen to set up housekeeping. But Legyria was infatuated with his talents as an artist. She had allowed him to join the vessel for however long it took him to accomplish his great work, that of sculpting in the very ivory of Esperance's living horn a frieze in the memory of the former captain, the famous Ellerios. Of course, Fentz was stretching out the work in order to remain aboard as long as possible. Orso avoided speaking to him, as much as was possible. All the same, in the situation he found himself in, it was impossible to ignore his presence.

"I love seeing the dawn rise on the desert," continued the sculptor, stepping gracefully around the bulging forefront of the vessel. "Don't you, Boson? But one would say you've found a new crewmember," he added as he pointed at the unconscious boy.

Orso eluded the question, saying "Bayu needs to examine him. I don't know if he'll live through the day, in the state he's in."

Fentz affected a grave air in replying. "It would be a shame to lose him, certainly. He could bring you a healthy sum."

Orso preferred not to commit himself to a quarrel. If it were up to him, the parasite would have swallowed his arrogance a long time ago, but Legyria had banned duels between crewmembers, Fentz included. Nevertheless, the day would come... Orso would even let him have his choice of arms.

"Can you tell the old man I need his services?" asked the boson. "Or are you too busy for that?"

Fentz smiled faintly and bowed.

"I would refuse nothing to our adjutant master on board, second only to our charming captain."

He had stressed the adjective pointing out the boson's place as subaltern. Once again, Orso had to force himself not to give in to provocation.

"Do it quickly. I haven't time to waste."

The sculptor leaped over Esperance's cranial bulge and disappeared through an opening they used at the base of the rostrum, where the circumference of the horn was widest. Orso remained a moment, contemplating the slow swaying of the prow, which matched the ship's crawl. As far as he could see, night was dissolving and giving way to the sparkling flames on the undulating lines of the horizon, highlighting the dunes near and far. In the first light of day, the desert seemed to be catching fire. A spectacle renewed every morning, and the display always amazed the boson. But he would rather cut out his tongue than avow to that parasite Fentz that they shared the same fascination!

An opening in the deck just under Orso's feet opened up at last, and Bayu's worn-looking mug appeared. His face looked like a piece of leather left too long in the sun, creased and shriveled. A few white hairs straggled over the round ball of his chin, and some yellowing locks of hair still hung over his splayed-out ears. It was hard to see where his eye sockets hid in that tangle of creases and wrinkles, let alone his eyes, but if you knew the geography of the wrinkles and lines on his face, you could find them. The burrower blinked rapidly several times, overwhelmed by the light of the dawn, before he could look at the boson.

"So it seems you need something from me?" he asked. "Hurry up and come in -- that damn light is ruining my eyes more surely than the stomach acids boiling in Espie's guts..."

Bayu was the only one on board to use this affectionate nickname to designate the ship. Doubtless because he was the oldest member of the crew, having been taken on as a simple deckhand by Legyria's grandfather. Since that time, he had held every imaginable position aboard, moving up through the ranks of the hierarchy, before finally settling into the post of healer and burrower. For Bayu offered his services to the men as well as to Esperance, whose organism he visited daily so he could do his collecting. From the innards of the living ship, he harvested the ingredients for his unguents, balms and cataplasms, culled from the intestinal and gastric flora of the animal. Nobody, not even the captain, could pride themselves on knowing "Espie" more intimately than Bayu!

The healer slipped back inside his den to let the boson enter. Orso went down the hatchway with prudent steps. The old man's den was filled with odiferous, almost palpable gloom. He waited for Bayu to close the hatch behind them and light the wick of a fluid lamp before he laid the refugee in a canvas hammock hanging at the back of the cabin. There was one porthole, on the starboard side, but it remained forever closed, with its round cover clamped down tight. Bayu adjusted the flame of his lamp until it diffused a halo of bluish light, barely sufficient to push back the shadows a few inches. Orso would have to be content with that.

The burrower leaned over his patient.

"Looks more dead than alive," he announced after a brief examination.

"He's still breathing," Orso said. "But just barely."

The fingers of the healer palpated the throat and chest of the boy.

"Life still circulates in the heart," he confirmed.

"Can you get him back into shape?"

"Well, there's more than one way to proceed," Bayu suggested, scratching the stubble of his beard between his thumb and forefinger.

Orso understood that the negotiations had just gotten underway. Nothing was ever free aboard a sand-sailing vessel. "I only want to get him on his two legs in time to get rid of him at a good price," he replied.

"But to get a good price, he must appear to be in excellent health."

The burrower had marked a point there. Orso sighed.

"What do you want in exchange for your services?"

"The right question is: what do you proposer to give me, Boson?"

Orso made a rapid inventory of his meager possessions. After having knocked about in company with mercenaries, and over numerous fields of battle, and then at the side of of Esperance's successive captains, he'd discovered that he was just as poor as the day he had left home, so many years ago. His sole capital consisted of an accumulation of memories, certain of them magnificent, others terrifying. That was worth all the riches in the world to him, but to the burrower? He may just as well offer the wind itself as payment.

While Orso was pondering the problem of payment, Bayu bent over the hammock again to give the boy a closer examination. Pointing at his canvas bag, he suggested:

"Let's take a look at what's in that -- perhaps we'll find something to satisfy me."

Orso agreed. The proposition was honest. Above all, it would offer the advantage of not costing him a thing if they made a lucky discovery. The belongings of the refugee belonged to him at this point, as did his life. This law figured at the top of the list in the unwritten code of the sand-sailors. And Bayu had mastered each and every one of its subtleties, to the point that he was called on to arbitrate in cases of conflict, and never had his judgments been brought into question.

As if by magic, a curved blade suddenly appeared in the old man's hand. Orso recognized it as a type of grating tool used to harvest the secretions of Esperance. With precise movements, the burrower sliced the straps of the bag. He then turned it upside down on a rickety table fitted up in a corner, which was already loaded with flasks and pots of all kinds as well as the remains of Bayu's last meal. Figurines in metal tinkled as they cascaded down out of the sack. Some were wrapped in strips of cloth, like fragile miniatures that needed particular protection. The boson's heart leaped. Had the kid got his hands on some treasure?

Bayu grabbed one of the pieces, in the shape of a strange beast gifted with four legs and an incredibly long neck, and stuck it in his mouth. After spitting out a brown wad on the ground, he shook his head and declared, "It's worth no more than its weight in lead, and that's as much as to say nothing."

The boson was disappointed, but curious also.

"What are they?" he asked.

"More than likely just toys, to amuse children," Bayu said. "But wait, there's something else sewed right into the inside of the sack."

With the cutting edge of the grater, the burrower cut out a piece of canvas, liberating a square, flexible object, the thickness of a bridge decking.

"Ah!" exclaimed the healer. "Now here's something interesting."

Clearing off a corner of the table, he placed his find on it, smoothing it flat, then he opened it up to reveal a stack of paper, each piece covered with designs in black and violet ink, and columns of writing so cramped that the figures appeared to meld and form one single word.

"You can keep the bric-a-brac, Boson. I'll take this."

Bayu closed the book back up with a dry snap. Orso shrugged to show his indifference. As was the case with most sand-sailors, he had never learned to read. An object like that had no value where they lived out their lives. So if the burrower was happy with that...

"It's a deal. The book will be yours as soon as the kid is on his feet. But if he dies, I take it back. I'll dig up some smart good-for-nothing who'll salivate when he sees these scribbles!"

"Agreed. Leave it with me in the meantime, would you? Maybe I'll be able to figure out what it's about -- you understand, just to pass the time between collecting samples."

Astonished, the boson asked, "You can read?"

The burrower grumbled with irritation.

"I didn't spend my entire life in the bottom of a stomach, nor waiting on Espie hand and foot, you know. To reply to your question, yes, I was taught my letters, but that was a very long time ago. So long ago, to tell the truth, that I no longer really remember."

"Well, stretch your memory as much as you like, just as long as you keep a good eye on the boy."

Bayu acquiesced. His face, of clay baked and re-baked, lit up with a caricature of a smile that looked more like a gaping wound than a grin.

"Take off his rags," he ordered. "You can throw them over the side - who knows what filth is hidden in the dirty folds of that shirt."

Orso acted without argument. The refugee's clothing nearly fell to pieces between his fingers, the fabric was so threadbare. The boson rolled them up into a compact ball that he stuffed into the pocket of his pants. Meanwhile, Bayu had greased up his calloused palms with a scoop of foul-smelling pomade, which he then rubbed energetically over the boy's limbs, giving extra attention to the spots where his skin was ornamented with bruises. Grimacing, Orso plugged his nose to avoid breathing in the atrocious stench of putrefaction.

"Rotten guts!" Orso exclaimed. "What is that made of?"

"Oh, just a bit of Espie's blood, mixed with some good oily earth instead of plaster."

"Blood?"

The healer laughed, with the shrill squeak of a rusty hinge.

"Weren't you aware that blood calls forth blood, you who made it flow so abundantly in your past?"

The dart barely touched the boson's hardened conscience. Coming from Bayu, it just scratched the surface. He knew it wasn't aimed to pierce the heart, as it would have been coming from that parasite Fentz's mouth, a mouth full of bile.

The healer became serious again as he explained. "I'm trying to revive the circulation in the poor boy's veins. I won't devise a treatment for the rest until I'm certain the fluid is flowing throughout his body. There's always time then ..."

Orso did not censure the burrower for his indifference - nowhere on the planet was a man's blood worth even a single drop of fluid, more precious than water, for though it was just as vital, it was far more difficult to procure. Instead, the boson said, "One would say the treatment is working. The kid is getting some color back."

The refugee's cheeks were in fact reddening with the influx of fresh blood. The results encouraged Bayu. He doubled his efforts. The boy's lips then began to tremble, his eyebrows to quiver as he was pulled from the limbo of unconsciousness.

He suddenly sat straight up in the hammock, with such abruptness that he almost fell out on the deck. His mouth opened to form a perfect oval. A cry erupted, a single sound, a simple word, which however, meant nothing to the boson:

"Izain!"

Then the refugee boy lost consciousness once again.

Chapter Three

Rumors of War

Fentz had not let slip a crumb of the conversation between the boson and the burrower. With his ear glued to the inner surface of the horn, the sculptor had caught the vibrations transmitted along the host's skeleton. He had gotten in the habit of playing the spy that way ever since his discovery of this phenomenon of sonorous propagation. It had come about, by pure chance, soon after he had installed himself in the rostrum. At first he had believed it to be an effect of the continuous rolling of the ship, an infinitesimal trepidation of the ram, more or less perceptible from time to time. Then he had had to accept the evidence: as he slept lying right on the ivory horn, faraway voices, almost inaudible, reached him every time his tympanum was in contact with the bony material. It had not really surprised him. Fentz had always been extremely sensitive to the variations of his environment. It was in this way he had developed his "artistic" temperament, which had made his glory and then his fortune, before leading him to his ruin...

But that was another story! And surmising from this morning's events, that story might just become ancient history, with a bit of luck and a whole lot of cleverness. A plan started to revolve in the sculptor's mind. A hope had taken root, that of reclaiming the better days of his past, when he was adulated for his talent, not obliged to hide in the holds of one of these horrible desert vessels in the hopes of being forgotten. He could no longer put up with the sand-sailors' vulgarity, nor with the captain's arrogance, though he always managed to hide his true feelings in their presence. It was so easy to fool them!

All the same, before acting he would still need to make certain he'd understood the import of the conversation in the burrower's den. To do that, a courtesy visit was required. Bayu always welcomed him. The old man appreciated his services; for example, when Fentz would inform him to break off his collecting by hammering in a precise spot of the horn, according to a code they had put into practice. Three short raps, repeated three times with a few seconds interval meant something urgent was up. Wherever Bayu was, even in the deepest stomach pouch, he never missed the signal, which reverberated throughout Esperance's bone structure. That was how Fentz had hastened the healer's return to his den earlier that morning, when that brute Orso had asked him to. Not to please him, far from it! No, if the sculptor had accepted to obey the boson so willingly, it was because he was curious about the refugee. This boy was perhaps his return ticket to the good life...

Once certain that Orso had taken his leave, Fentz went to knock at a panel of the hatchway cut into the forecastle, which led into the healer's den. As usual, the sand-sailors working on the bridge paid him no attention. All the better, thought the sculptor, keep scouring and polishing without a thought for the one you consider a parasite -- you'll soon have more to be preoccupied with if everything comes out as I plan!

"Oh, is it you?" Bayu said as he lifted the panel a few inches only. "What do you want? I'm rather busy."

"I know. The boson's new protégé is giving you more work than ever. That's why I've come to propose giving you a hand."

"And your own work?" the burrower asked, full of surprise.

Fentz was ready for the objection. "I've just finished a boarding scene and I'm still hesitating about the next scene. I was thinking that we could talk about it together while taking care of the stranded child. You are the memory of Esperance, Bayu. Your stories are my best source of inspiration."

His flattery won Bayu over, as Fentz had expected. The healer's creviced face reddened with pleasure as he responded. "Well, come in quickly then. I was just thinking of an interesting anecdote about our old captain. As you perhaps know, Ellerios was a famous tippler, and one night at an oasis where wine flowed like a river, it just so happened that..."

Fentz suppressed a smile as he followed the old man, who had begun to babble, only too happy to air his memories even if for just one listener. This was going to be easier than he'd thought!

*

"What's worrying you, Captain?" Orso asked. "Is it the kid I brought on board?"

Legyria pushed her hair away from her face but did not turn her eyes away from the line of the horizon.

"I don't care about him," she said. "You'll soon have exchanged him for a handful of gold pieces and nothing more will be said. No, I'm thinking about something else..."

She interrupted herself, as if slamming shut and triple locking the door to her thoughts. Legyria did not like to share her anxieties or concerns, thinking that confiding in others would amount to exposing a weakness. No captain worthy of the title would ever allow that to happen!

But Orso was not fooled. He had seen the girl grow up into a young woman, and he could read even the slightest changes in her expressions. Like that tight fold at the corners of her lips now - that meant she was upset about something.

Legyria directed sailing maneuvers from the quarterdeck, and that's why he'd come to look for her there, because the second he'd put a foot on the bridge after meeting with Bayu, he'd realized they had deviated from their course. The curve in the vessel's wake confirmed it: Esperance had put her head to the north.

To get her talking again, the boson took advantage of the change of course as a new topic. He was, after all, still the clever dog of war he'd always been.

"I saw you changed our course. Where's our next port of call?"

He could see her starting to waver, and he decided to wait patiently - you don't push your captain, who has power of life or death over crew and vessel, Legyria was the last of her line. The hereditary link that united her to Esperance guaranteed her authority as captain, and she alone had the power to change the vessel's course. Without her, the enormous animal would end up left to its primitive instincts. People said that without a pilot, these creatures would wander haphazardly into the most inhospitable regions of the desert, using up all their energy reserves, until wasting away in the fiery sun and being buried by the dunes. No sand-sailor doubted the truth of this. These vessels prospered under the dominion of a master, who knew how to guide it from oasis to oasis, where it could absorb the fluid crucial to its survival. It was as simple as that. As to the fashion in which the link between captain and vessel worked, it was a bit more complicated. On this very quarterdeck, Orso had seen Captain Ellerios snap out orders without uttering a word, just by moving his powerful arms, orders that Esperance had obeyed to perfection. The old captain's daughter preferred to give orders more subtly, without an extraneous gesture, but she was just as efficient. She kept herself to subtle movements of the tips of her fingers, or by raising a hand in the air before her nose, as if tracing invisible words on the infinite desert panorama. And maybe that was just how she proceeded, for all the boson knew!

Finally, Legyria whispered, "Baas'abell."

Orso's eyebrows shot up his bald skull.

"It'll take an extra two days to reach," he said. "There are other oases much closer, and safer too."

Baas'bell had a reputation as a dangerous spot. Because of the town's unique location - at the edge of the desert and the steppe, on the banks of the Ouros, the largest river to water the territory - it attracted all that the continent held of ruffians and mercenaries, over and above the usual merchants and transporters. In particular, its river port provided anchorage to scores of steel ships, and as everyone knew, pirate steamers formed the largest part of the fleet.

Baas'bell marked the northern limit of the sector crossed by the desert vessels, which never travelled beyond the Ouros, so for Legyria to risk stopping there meant she must have an excellent reason. But how to draw it out?

"I could more easily explain to the men what they're getting into if you would confide in me," Orso insisted. "They'll be asking me all kinds of questions straight away."

Legyria now looked directly at her second in command. The boson would have preferred facing two adversaries determined to rip him apart rather than meeting her eyes! The very sky would be jealous of such a vivid blue, so like the color of the ocean that they unnerved a sand-sailor like Orso, who was convinced of the evil nature of the liquid element.

"I spoke to the other captains during our last halt," Legyria began.

Orso nodded. He remembered those meetings. While the crewmembers cheerfully drank and spent the last of their pay before having to report back to duty, the meetings had gone on in tents set up in the middle of a garden. Esperance had delivered her cargo of spices within the time designated by the buyer, one of the numerous tribal chiefs who lived to the rhythm of the dunes' perpetual shifting. This chief had shown himself to be quite generous and the party had lasted until dawn.

Legyria, as was her habit, had not participated in the revels.

"They spoke to me of disturbing rumours that have reached them," she said. "Sand-ships have been attacked."

"By pirates?"

"No, they've been relatively quiet lately. They're waiting to see how best to take advantage of the crisis on the horizon."

"What crisis?"

"There's talk of war, Boson. The tribes are arming. In the south, fluid is becoming scarce."

Orso suddenly understood where his captain was leading.

"And you said to yourself that here's an opportunity to make a nice profit," he finished. "Profitable because it involves a rather perilous mission. Even suicidal."

Cold light illuminated Legyria's gaze for a brief instant.

"Don't try to give me lessons, Boson. I know the risks we'll have to run, and I haven't yet made my decision. But with all these rumours of imminent war, the freighter captains are thinking twice before sending out new cargo. Already business is not exactly booming for us..."

"Didn't you make enough with that cargo of spices?"

"Barely enough to pay the crew and buy a little fluid to feed Esperance. Several sources of production have dried up, and prices are skyrocketing. In the South, certain people are ready to pay us a fortune if we can manage to bring enough down to them. Because the side with the largest stock of fluid will win the war."

Orso reflected for a moment.

"Let's admit you're right. The journey could be worth a try. But what shipper would be crazy enough to place all his money on such an expedition?"

Legyria's expression softened with a smile when she answered. "You think I haven't considered that? Just you wait, I might have the right person in mind."

She would say no more, and that was frustrating for Orso. He wanted her to reveal the name of that "right person," but he did not persist. The young woman had recovered her taciturn and mulish look. It would serve no purpose to try to pry anything out of her.

The boson made a detour to his sleeping pouch to deposit the objects he'd recovered from the refugee's bag. The half-dozen strange figurines intrigued him. Orso had never seen creatures like these, cast in poorly-fabricated lead. They must have been toys the boy was attached to, or else why would he have lugged them along? But what were they supposed to represent? As soon as his ‘protégé' could talk, the sand-sailor would certainly ask him about them.

Meanwhile, he hid the objects safely in his own bag, and then went back up to the bridge to take his post.

*

"...and that's how Ellerios lost half of his little finger without even realizing it!" concluded Bayu, smothering a laugh that sounded like an avalanche of gravel in a dry streambed.

Fentz satisfied himself with a polite nod. He had followed the burrower's recital with a distracted ear. His attention was fixed on the child, now sleeping peacefully in the depths of his hammock. Bayu's balm had produced a calming effect, and the plasters had cauterized the wounds opened by the vulture's claws. For the rest, the healer had declared that a few good meals would suffice to put a bit of flesh on his protruding bones and fill him out.

"So, what do you say? It's rather a good story, isn't it? Worthy of figuring somewhere on Espie's horn, I'm sure of it!"

"If our captain has no objection, it will be so," the sculptor said, eluding the question.

Despite a detailed observation of the boy's features, Fentz had not been able to form an opinion about him. His ordeal had sunken his cheeks and the sun had made no concession to his tender age: his skin was burnt and already peeling, to the point of erasing some details. But his general physiognomy could very well correspond with the description the sculptor had kept in his memory, even if he had heard it only once, many years ago, and only briefly at that.

Fentz was hardly about to forget that memorable evening! It had taken place in the villa of his old protector, where the local elite regularly got together. Artists, merchants, clan chiefs and other persons not so easily categorized, but who all shared the same passion for intrigue and liked nothing better than to weave the destinies of their less-influential contemporaries. Above all, a fabulous wine had been served that night, without stint, to all the guests. With a full cup in hand, and being careful to keep it that way, Fentz had wandered from group to group, listening in and gathering bits of conversation.

He had already heard of the fable of the Founder of the first oasis. He had even consecrated some of his most admired works to the legend. But it was the first time anyone had mentioned, in his hearing, the legend of the Founder's return in the form of the ‘Child of the Book.' Intrigued, he had eavesdropped shamelessly on the old men who were speaking in low voices of what they knew. One of them, a stranger just passing through the region, seemed convinced that the myth was to come true. Although Fentz's brain was a bit foggy from the alcohol, he still got the message: the old man was affirming the existence of a cult and its avatars. Holding such beliefs immediately thrust him into the ranks of superstitious barbarians, the likes of those who still survived in the South.

But what surprised Fentz most was that the other old men did not mock the stranger for his belief. On the contrary, they seemed to be quite impressed by a medallion that the stranger was wearing around his neck, hidden under the folds of his mantle. The sculptor had taken his turn to stoop and look with curiosity at the small piece of corroded metal soldered onto a gold chain. It was obviously very old, almost certainly dating back to the first days of the oases. You could still distinguish a face in three-quarter profile engraved on its surface, the face of a very young man.

"It's Him," the stranger had whispered, his voice vibrating with respect. "Him, such as He was and as He will be again, as many times as need be throughout the course of the centuries," he had added, without giving any more explanation to these mysterious words. Fentz had forgotten what happened afterwards. Perhaps he had been rather drunk, he said to himself wryly. But his artist's eye had imprinted, in a corner of his mind, every last detail of the medallion. And today, he was trying to make a connection between the face of the child before him and the Founder of the medallion. He could see no clear resemblance, however. At the boy's young age, the flesh is still malleable, and the vagaries of life have not yet modelled it according to its circumstances. But he couldn't deny a vague resemblance, sufficient in any case for Fentz to convince any zealous followers of the Foundation cult that "He had finally returned." And seeing as how most of those ‘illuminated ones' wanted only to be convinced, it would be only too easy!

Plus, if the sculptor presented them the book as an additional proof, he was sure to persuade even the most sceptical of them to believe his theory. His orator's talent would make all the difference. After all, it wouldn't be the first time - or the second or the third - that he had hoodwinked the people around him; in fact, one of those little tricks had been the cause of his fall from grace...

Fentz tried to make out where the book could be in the unholy mess of Bayu's den, but he did not see it. Useless to ask the old man where it had gone. That would seem suspect. The burrower must have hidden the book to prevent any indiscreet glances. Fentz would have to figure out how to get his hands on it before their next stop, but in utmost secrecy. That implied further visits to the healer and more boring anecdotes, but that would be a small price to pay in comparison to the profits he hoped for. That is, if his plan unfolded without a hitch! The perspective of sweet revenge drew a smile from the sculptor. He took leave of Bayu with the promise of returning soon to ‘commiserate with the wretched, sick child.'

"Poor boy, I can't wait to hear his story, I'm sure it will go straight to our hearts!"

Translated by Galatea Maman